Action Day at Who Owns Brighton

- Anke Schwittay

- Jul 16, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 6

A few weeks ago we held an Action Day for our Who Owns Brighton (WOB) research project, which was launched by the Brighton and Hove Community Land Trust back in January. The purpose was to share what four different groups of community researchers had learned about the development of Circus Street, focusing on the history of the area, its present-day residents, planning processes and financial arrangements. Thank you to everybody who participated in the research! Here are some highlights from the day. You can also watch a short video about the project.

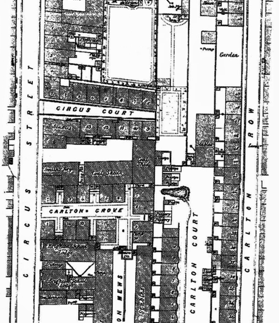

A history of clearances

The History group chronicled the origins of the area as a riding school, before it became home to small merchants, their families and shops, all tightly packed together. There were repeated cycles of slum clearances starting in 1897, less than 100 years after the original houses had been built. A second wave followed in the 1920s and 30s, which demolished around 900 homes, mainly of poor seasonal workers and small merchants. The area was also severely bombed during WWII but that did not stop the municipal fruit and vegetable market, which had opened in 1936, from thriving there until it closed in 2005. For a few years, the market space became home to community arts exhibitions and performances, such as Theater Uncut, in response to the Conservative government's austerity cuts to arts programs. Others remembered the violence of immigration raids, which also took place during the construction of the current development. We also watched clips from a video where market traders shared their memories, with some of the most vivid ones being the sounds of the market. This stood in marked contrast of the experience we had during the Listening workshop, where the quiet of Circus Street had struck us most of all.

The new slum?

The People research group had undertaken several community listening sessions involving 42 people and administered a short questionnaire to dozens more, including students living in the Kaplan residences, residents in the shared ownership Courtyard Apartments and also in the Milner Flats, a block of social housing built in 1934 and now situated right behind the development. The latter were severely impacted by the construction, as the photos below show, and are still affected by a loss of light and privacy as well as noise from the student accommodations. The residents spoke of broken promises and their close community feeling like 'the new slum.' For Courtyard residents, the low built quality and the massive increase in service fees were the biggest drawbacks, with some being trapped in their homes unable to sell them. There was also a lack of community, with many of the retail spaces being empty due to insufficient footfall - the South-East Dance Space being the only exception to that. This is all a far cry from the promises that were made during the planning stages of the development.

From Circus Street to Wall Street

The Process group reported that the number of affordable homes to be delivered on the site had declined throughout the process of planning and building Circus Street, a public-private partnership between developer U+I and Brighton & Hove City Council. Other parameters, for example about density and height, were never properly debated but instead taken as givens in planning applications. The architecture firm Shedkm, a regeneration specialist based in London and Liverpool, wanted to emulate an industrial feel that also took the site's history and Brighton's 'vibrant' character into account. The power of the City Council to shape the development seemed very limited because vital decision were baked into its various processes and assessments. The result is a real mismatch between what has been promised and what exists now, as seen in the architect's drawing and photo below.

Another guiding principle of the development was anxiety about decline and dereliction if nothing was done with the site. To show that 'doing nothing doesn't mean that nothing is happening' the group finished its presentation with a nod to Hastings Commons, a Community Land Trust in Hastings that develops derelict and difficult buidings through community custody, among them the Harpers Caves and Alley Gardens, shown below.

Finally, the Money group had traced the financial flows from Circus Street to Wall Street, showing a gradual shift from family firms that owned the area's properties to global financial companies organized into complicated trusts and structures that are hard to track. Names like Blackstone, BlackRock, and Vanguard are not only dominating housing and real estate investments in this development but others in the UK and internationally. The University of Brighton, which has experienced extreme financial difficulties and rounds of lay-offs in recent years, had pulled out of the development in 2017 but still owns the small green space that could be considered the only public area, earmarking it for future use.

In the subsequent discussion, participants shared their negative feelings about much of what they had learned. There was also anger at especially the exploitation of young people (students, who pay over £250 week for small rooms in the Kaplan accommodations, making student housing highly profitable) but also the first-time home buyers who managed to buy homes through 'affordable housing' shared ownership but are now stuck paying unaffordable service fees. We asked where the accountability is when developers are not delivering on what they promised, beginning with truly affordable homes but also with a lively, 'buzzing', vibrant and friendly neighborhood, of which Circus Street seems to be the total opposite (with the exception of the Dance Space).

Where to next?

However, part of the project has always been to identify possible points of intervention and this was an Action Day, so our discussions turned to thinking about possible ways forward:

There is small community of resistance forming against the service fee exploitation, and we discussed how our findings could support that struggle. This could includbuilding a broader coalition by bringing affected home owners together with Milner Flat residents who have also been negatively affected by the development. An event to share our findings with the residents is being planned already.

Another idea was around stopping the small green space from being developed by the university or more likely parties to whom the space will ultimately be sold. This could be done in collaboration with the university's architecture students working on possible life projects.

Participants were also interested in conducting more research in other sites in the city, to see if the patterns of development are repeated there. Another aim is to build more evidence to present to the council and other stakeholders, also to create more avenues for accountability. A larger funding proposal is in the works to enable this to happen.

We talked about creating a toolkit for other groups to emulate the participatory research process.

Most immediately, we are working on sharing our findings: a short film to document the project is in the editing stages, posters are being created by graphic designer Soofiya Noor and events are being planned for late summer and autumn, including a large community event in the second half of October. So lot's more is to come, and the best way to learn about it is to join or follow the Brighton and Hove Community Land Trust.

We would like to thank everybody who has participated in WOB, as community researchers and workshop participants. The project, which is carried out in partnership with the Universities of Brighton and Sussex, has been supported by the Civic Power Fund, and the Action Day was made possibly by funding from the University of Sussex Knowledge Exchange and Innovation Fellowship Fund.

Comments